A Critique of the Argument for Indirect Realism

I will call it “The Argument”. It assumes many guises and has survived for hundreds of years, and I would like to explain what I think is wrong with it. Here is a classic instance, from David Hume in his 1748 Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding:

It seems also evident, that, when men follow this blind and powerful instinct of nature, they always suppose the very images, presented by the senses, to be the external objects, and never entertain any suspicion, that the one are nothing but representations of the other. This very table, which we see white, and which we feel hard, is believed to exist, independent of our perception, and to be something external to our mind, which perceives it. Our presence bestows not being on it: our absence does not annihilate it. It preserves its existence uniform and entire, independent of the situation of intelligent beings, who perceive or contemplate it.

But this universal and primary opinion of all men is soon destroyed by the slightest philosophy, which teaches us, that nothing can ever be present to the mind but an image or perception, and that the senses are only the inlets, through which these images are conveyed, without being able to produce any immediate intercourse between the mind and the object. The table, which we see, seems to diminish, as we remove farther from it: but the real table, which exists independent of us, suffers no alteration: it was, therefore, nothing but its image, which was present to the mind. These are the obvious dictates of reason; and no man, who reflects, ever doubted, that the existences, which we consider, when we say, this house and that tree, are nothing but perceptions in the mind, and fleeting copies or representations of other existences, which remain uniform and independent. [1]

Hume’s argument from perspectival variation is just one among many similar arguments which all purport to prove the two-part doctrine of indirect realism: that in perception we are not aware of the things we naively suppose ourselves to be aware of — tables, sunrises, chickens and people — and that the things we actually are aware of are perceptual intermediaries of some sort, mental objects often referred to as “representations” or similar. The venerable arguments from illusion, from double-vision and from hallucination are all versions of The Argument.

I am not the first to criticize The Argument, and it might seem like an easy target. So why am I picking on it?

Perception, for better or worse, has been at the heart of modern philosophy, and this tells us something about how, in the wider culture, we have come to see ourselves since the rise of science. There is a historically specific picture of perception lying in the background and making it possible for The Argument to seem persuasive. Like everyone, I feel the pull of the Cartesian starting point in philosophy: I am a thinking thing, a thing in the head, with accidental body parts, acquainted first and foremost with the contents of my consciousness, sometimes opening my eyes to passively contemplate the properties of a table, as represented within me by a special kind of mental object. I am fascinated by the way that this became part of our everyday thinking.

A more down to earth reason for my interest is that it is topical. The still-raging battle in the world of cognitive science between computationalism and embodied cognition hinges on the philosophy of perception and mind. For computationalists, the appropriate level for a mathematical model is the individual agent’s mental manipulation of representations constructed from raw inputs that happen to impinge on its sense-organs. In contrast, those who take the embodied approach model the agent-environment system on the basis of dynamical systems theory, in which the agent is not treated alone but rather as coupled to its environment. This split is fundamentally a philosophical one, between indirect and direct realism, respectively.

Hume’s Version

The Argument is presented in Hume’s Enquiry, as in all other cases, as a philosophical correction to the common-sense view that we perceive the external world without perceiving anything intermediate. I will call the common-sense view naive realism, and refer to its philosophical elaboration and defence as direct realism (setting aside the rightful objection that it is misleading to take an unconscious common-sense presupposition as being a positive philosophical position, i.e., a “realism”.)

Notice that in the first sentence quoted, Hume seems already to posit “images, presented by the senses” as the immediate objects of perception. This assumption is not argued for elsewhere, and is very close to the conclusion of the whole argument itself. In one sense this might be a pedantic or off-target criticism, because Hume might just be presenting his conclusion before proceeding to argue for it. However, this odd assumption is introduced with such ease and confidence, and repeated for rhetorical effect up to the point where the argument proper begins, that it is reasonable to be suspicious.

Incidentally, I appreciate that it is stupid to point and laugh at the great thinkers of the distant past, and that it is ahistorical to identify formal arguments in old texts, rip them out of context and put them under the microscope. In criticizing Hume I hope not to be engaging in such stupidity and anachronism. What I hope I am doing is questioning the anachronism of those who remain bewitched by these arguments, in ignorance of the intellectual background that made them so persuasive. Thus the reason I am identifying an argument at all, in what is presented by Hume more as an obvious result of philosophical reflection in the context of everything else he has said in the surrounding text and in his Treatise, is that this is its legacy.

So if we are to construct an argument out of it, it will have to go something like this:

- Premise 1. The table seems to diminish as we move away from it

- Premise 2. The table does not really diminish as we move away from it

- Conclusion 1. Therefore when the table seems to diminish it is not the table itself which is the object of perception

- Conclusion 2. Therefore the object of perception is a mental image, copy or representation of the real table

The trouble is that the negative Conclusion 1, on which the positive Conclusion 2 depends, does not follow from the premises. To complete the argument we must introduce a missing premise, so that we end up with this:

- P1. The table seems to diminish as we move away from it

- P2. The table does not really diminish as we move away from it

- P3. If there sensibly appears to a subject to be something which possesses a particular sensible quality then there is something of which the subject is aware which does possess that sensible quality[2].

- C1. Therefore when the table seems to diminish it is not the table itself which is the object of perception

- C2. Therefore the object of perception is a mental image, copy or representation of the real table

The argument requires this extra premise to secure the conclusions because without it we are free to say that although the table seems to diminish, it really does not, and furthermore there is nothing else that diminishes. Intuitively, seemings are surely not distinct objects themselves, or properties thereof, and need not always pick out real objects and properties — obviously, to seem to be so is not to be so. P3 must therefore be included to assert that what seems to be the case is in fact the case, viz., that when the table seems to diminish, there is indeed something seen that is table-like and increasingly small (the object which was naively taken to be a table).

P3 has recently become known as the Phenomenal Principle, courtesy of Howard Robinson, who defends a sense-data theory in his book Perception. How plausible is it? J.L. Austin thought not in the least, calling it “completely mad”. Austin’s response to Ayer’s bent-stick formulation of the argument from illusion dispenses with it in short order:

If, to take a rather different case, a church were cunningly camouflaged so that it looked like a barn, how could any serious question be raised about what we see when we look at it? We see, of course, a church that now looks like a barn. We do not see an immaterial barn, an immaterial church, or an immaterial anything else. [3]

Applying this to the present case we can say that in seeing a table apparently diminish we are not seeing anything actually diminish. We are, at most, seeing a table that looks like it is diminishing.

The requirement for the Phenomenal Principle points to an unexamined presupposition, namely that mental images are all that we ever see. Thus when the premise is made explicit it can be seen to depend on the conclusion of the whole argument, for why else would we assent to the existence of a diminished object of perception, as implied by P3, except under the assumption that we always perceive mental objects? The argument looks like a simple case of begging the question.

Even if we try to regard the appeal of the Phenomenal Principle more sympathetically, at most we might say that because the process of perception always works in the same way and does the same thing, it can seem reasonable to say that it must be directed always at the same class of objects. But this is surely no more intuitively correct than to say that perception sometimes goes wrong, and not because some mental objects of perception are more representative than others of the external world, but just because the senses do not always make contact with the world successfully. In any case, considerations of the process of perception begin to edge into optical, physiological and neurological descriptions. I will say more about that below.

I want to mostly avoid linguistic analysis in this article, but it is worth examining for a moment the word “see”. We can distinguish between (1) seeing a table, and (2) seeing a scintillating scotoma, with corresponding uses of the word “see” that I will label see(1) and see(2). The first is used in reference to perception, but the second is about mere appearances, in this case caused by a neurological anomaly affecting parts of the brain connected with perception, subjectively manifested within perceptual experience. Can it really be intuitive to say that because the scotoma is not an external object, the table that I see is therefore not an external object either? Appearances can be deceptive, but it does not follow that we always only see appearances, because, as with “see”, “appearance” can be used in various ways as well. Perhaps we can say that the scotoma, which I see(2), is an appearance, or even a mental object. But the appearance of the table, in contrast, is just the way that I see(1) the table, and is not itself the object that is seen(1). Therefore, we only see(2) appearances when there is nothing out in the world to see(1); and such appearances cannot count as objects of perception, so there is no single class of objects to which awareness is directed in every case, because sometimes it is not directed at any objects at all.

Sensation

But surely there must be a diminution when I walk away from the table, if we are to accept the findings of physiologists and psychologists of vision, the significance of optics, and even our own experience. Something is getting smaller.

We can describe this real diminution in physical or geometrical terms. Something like the following: when I walk backwards away from the table, the reflected light from the table subtends an increasingly small area of my retina. But I want to quickly dispense with the idea that such scientific descriptions entail anything like indirect realism. We can reconstruct the argument in such terms, thereby getting rid of the references to experience in the premises. We can do this by replacing the first premise and reformulating P3:

- P1. The light from the table subtends an area on the retina of diminishing size as we move away from it

- P2. The table does not diminish as we move away from it

- P3. If an object casts light subtending an area of diminishing size on the retina, then there is an object that is diminishing in size (the patch on the retina)

- C1. Therefore . . . what?

For the sake of argument we can waive any objections to P3 and take the object which is diminishing to be the patch of light on the retina, with the proviso that this is not regarded as the object of perception. But now there is no argument left. The conclusions of indirect realism do not follow from these premises, indeed they have little to do with them. And notice that P3 no longer states the Phenomenal Principle, because premises P1 and P2 in this case say nothing about what is seen. That is, they say nothing about objects of perceptual awareness as such. We see by means of a shrinking patch of light, but this patch is not what we see. The alternative to this is to confuse different kinds of description and say that, for example, we only ever see the images on our retinas, or hear the vibrations of our eardrums, or smell our noses. Of course, we see with our retinas, hear with our eardrums, and smell with our noses.

So the diminishing area on the retina is quite consistent with perceiving a real table directly; that is, perceiving a real table without perceiving an intermediate mental object. Physiology and optics give us no reason to doubt naive realism, because the latter is not a position on physiology and optics. This cannot be the argument that is intended.

Russell’s Version

Bertrand Russell, in The Problems of Philosophy, considers several of the ways in which—to use his words—the appearance of a table is different from the reality of the table. One of them is shape:

We are all in the habit of judging as to the ‘real’ shapes of things, and we do this so unreflectingly that we come to think we actually see the real shapes. But, in fact, as we all have to learn if we try to draw, a given thing looks different in shape from every different point of view. If our table is ‘really’ rectangular, it will look, from almost all points of view, as if it had two acute angles and two obtuse angles. If opposite sides are parallel, they will look as if they converged to a point away from the spectator; if they are of equal length, they will look as if the nearer side were longer. All these things are not commonly noticed in looking at a table, because experience has taught us to construct the ‘real’ shape from the apparent shape, and the ‘real’ shape is what interests us as practical men. But the ‘real’ shape is not what we see; it is something inferred from what we see. And what we see is constantly changing in shape as we move about the room; so that here again the senses seem not to give us the truth about the table itself, but only about the appearance of the table.

After similar considerations with regard to colour, visible texture, and touch, he concludes as follows:

Thus it becomes evident that the real table, if there is one, is not the same as what we immediately experience by sight or touch or hearing. The real table, if there is one, is not immediately known to us at all, but must be an inference from what is immediately known. Hence, two very difficult questions at once arise; namely, (1) Is there a real table at all? (2) If so, what sort of object can it be?

It will help us in considering these questions to have a few simple terms of which the meaning is definite and clear. Let us give the name of ‘sense-data’ to the things that are immediately known in sensation: such things as colours, sounds, smells, hardnesses, roughnesses, and so on.

[…]

Thus what we directly see and feel is merely ‘appearance’, which we believe to be a sign of some ‘reality’ behind. [4]

Even though the conclusion follows only after considerations of several other qualities of the table, these serve merely to reinforce one another for persuasive force and generalization, so I think we can with fairness reconstruct Russell’s argument with respect to shape alone:

- P1. The table looks as if its top has two acute angles and two obtuse angles

- P2. The tabletop’s real shape is rectangular; it does not really have two acute angles and two obtuse angles

- P3. If there sensibly appears to a subject to be something which possesses a particular sensible quality then there is something of which the subject is aware which does possess that sensible quality

- C1. Therefore the real table is not what we see

- C2. Therefore what we see is a mental image, copy or representation of the real table

Russell is here making the same argument from perspectival variation in the twentieth century as Hume made in the eighteenth. Again, for the argument to work it requires P3, the Phenomenal Principle. For we could say without contradiction that even though the table’s apparent shape is not its real shape, yet it is the real table that we see, but from a different perspective. After all, it is surely no surprise that things look different from different perspectives. And contained in that fact is the thought that it is the things themselves that look different.

Russell must be demanding that, in order to be direct, perception must live up to a standard whereby tables with square table-tops always reflect light on to our retinas to produce a square geometrical projection. Clearly, this standard is an impossible one to live up to.

Perceptual Constancy

I’ve been accepting for the sake of argument that the table appears to get smaller as we move away from it and change shape as we move around it. But does it? I hope to show that this question is not as silly as it might appear.

Rephrasing it might reveal the problem. Do tables seem to shrink as we move away from them? Do they appear to metamorphose as we walk around them? Do coins or frisbees look elliptical most of the time? Does the man at the other end of the room look four centimetres tall? I think the most reasonable answer to these questions is no. In my last example, if the light from the man at the other end of the room subtended the same area on my retina as he would if he were standing right in front of me, I would think he was a giant. He would look gigantic. And if the geometrical projection of the apparent shape of the table-top was square when seen from a few metres away, the table-top would not look square. It is for the very reason that perspective results in projections of light on the retina which vary in size and shape that I can see objects as constant in size and shape. In psychology this is called perceptual constancy, and it has been extensively studied.

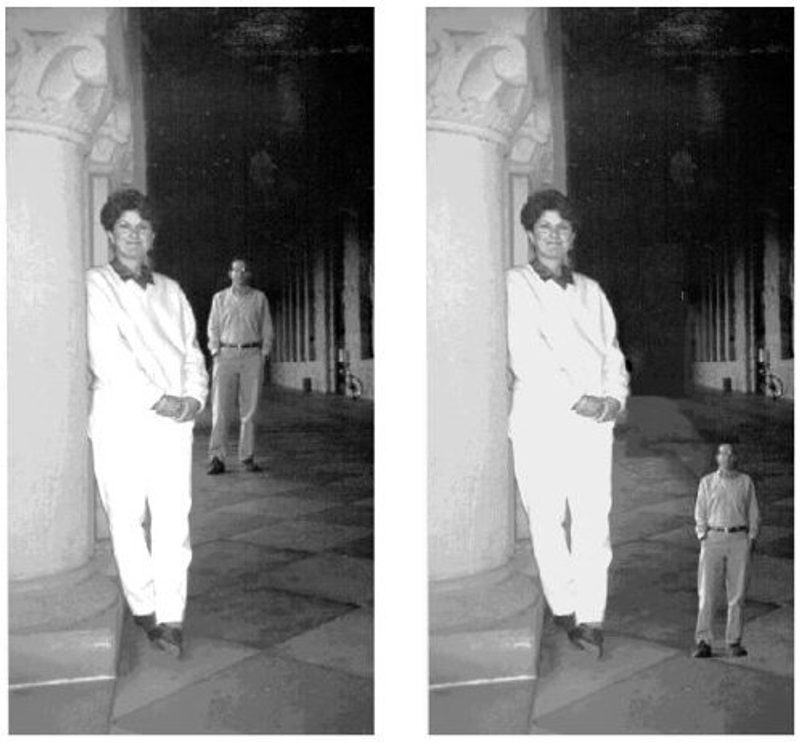

In this image, can it be right to say that the man in the left-hand photograph looks tiny compared to the woman? I am confident that most of my readers would instead say that he looks normal size, and perhaps a few centimetres taller than the woman in the foreground. He does not look tiny precisely because we can see that he is standing some distance away. In the right-hand photograph he seems to be standing where the woman is standing, with the result that the projected spatial dimensions which do not make him look tiny in the realistic photograph do make him look tiny in the manipulated photograph. That is what it looks like when it looks like objects are tiny. [5]

But sometimes we can snap out of our normal way of seeing, such that the coin’s surface does look elliptical or the man at the other end of the room, when we measure him with our fingers, does look four centimetres tall. When we do this we are attending to the geometry of seeing; most often we do not see things in this way. As well as this intentional, forced failure of perception, we can find ourselves in situations where our perceptual constancy is stretched to the limit and broken. While the man at the other end of the room does not look four centimetres tall, from the top of the Eiffel Tower the people on the ground really do look like ants.

One objection — and this is clearly Russell’s view — is that we infer the real shape and size of objects based on what we see. The following passage from Heidegger suggests why this might be the wrong way of thinking about perception.

We never . . . originally and really perceive a throng of sensations, e.g., tones and noises, in the appearance of things . . . ; rather, we hear the storm whistling in the chimney, we hear the three-engine aeroplane, we hear the Mercedes in immediate distinction from the Volkswagen. Much closer to us than any sensations are the things themselves. We hear the door slam in the house, and never hear acoustic sensations or mere sounds. [6]

Normally, I am immediately aware of the true sizes and shapes of objects (unless I have “snapped out” of normal perception). And recall that it is the nature of this perceptual awareness that is at issue, the physiological process being mostly irrelevant—a black box of naturally evolved tricks. It is difficult, then, to see how one can reasonably use the term “inference” to describe an integral part of the process of perception, namely perceptual constancy, which is subsumed in the act of seeing, i.e., being visually aware of, external objects. An inference is deliberate, conscious and rational. Perception, by contrast, happens automatically and mostly without deliberation. One can introduce the notion of inference here again only on the assumption that what we immediately see in perception are representations or sense-data, from which — once we’ve done the perceiving — we can infer what’s really out there.

This is the duck-rabbit, made famous by Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations. Notice that we switch between exclusive ways of seeing it, now as a duck, and now as a rabbit. This is termed multistable perception, and it does not fit very well with the notion that we infer a duck or a rabbit from neutral stimuli. It is not because we analyze the picture, checking off its properties against a mental database, that we see it as a duck or as a rabbit. Rather, we immediately see it as a whole, excluding other ways of seeing it at any instant. In doing so we directly see what is significant or what has meaning, and exclude the rest. Perceiving as this or that is built right in to perception. This is a clue to a big problem with The Argument, namely its underlying assumption of a structure of perceptual experience with (a) a static, passive and purely sensory gathering of stimuli, combined with (b) rational deliberation on the representations that result from these sensations. The task of bringing out the problems with this view, and supplying a better picture of perception, will have to wait for a future article. I think we can at least say that twentieth century psychology and philosophy have given us good reason to think about perception differently.

Now it might be wondered how perception can be said to be anything but indirect if we can switch between ways of seeing things while those things do not change. Does this not lend weight to the thesis that what we see are, even if not neutral sense-data or the inferences thereof, then aspects which are constructed by the brain? I do not think so, because such cases cannot be taken as the paradigm of perception. The specially crafted multistable illusions force a “snapping out” of normal perception in the sense used above, such that we “see” a duck in the sense that we “see” a scintillating scotoma, only in this case it is an apparent quality of something external. It might help to think of it as a consistent hallucination.

A General Form of The Argument

Back to The Argument. Now might be a good time to construct a general version of it.

- P1. There appears to be an X which is Y

- P2. There is no X which is Y

- P3. If there sensibly appears to a subject to be something which possesses a particular sensible quality then there is something of which the subject is aware which does possess that sensible quality

- C1. Therefore when it seems that there is an X which is Y, there is no X which is the object of perception

- C2. Therefore the object of perception is a mental object

- [P4. The Principle of Subjective Indistinguishability]

- C3. Therefore the objects of perception in all cases are mental objects

The optional premise P4, what I am calling the Principle of Subjective Indistinguishability, covers arguments such as those from illusion and hallucination. In the case of illusion the principle produces the following premise:

There is no non-arbitrary way of distinguishing, from the point of view of the subject of an experience, between the phenomenology of perception and illusion. [7]

C1 is the negative conclusion, C2 the positive conclusion, and C3 is the explicit generalizing move, which in the case of illusion and hallucination is made possible by the inclusion of P5. Again, note especially that P3, the Phenomenal Principle, is required not only to for the positive assertion in C2 of the existence of mental objects, but also for the negative conclusion in C1. One can only conclude that the real X is not what we see if one accepts that there must be an object possessing the qualities which are apparent in perception.

To reiterate: the persuasiveness of the argument comes down to the plausibility of Phenomenal Principle. Is it more plausible than the alternative explanation, namely that although X looks Y, it is not Y (or, although it looks like there is an X which is Y, there is not really an X which is Y)? It surely must be agreed by the indirect realist that this is not an immediately troublesome notion, that what seems to be the case is not actually the case. On the face of it there is no need to posit an extra object. Now, it has been claimed (Robinson) that the Phenomenal Principle is intuitively right, but the problem, it seems to me, is that it is intuitively right only to those who have already absorbed the doctrine of indirect realism. What reason for accepting the Phenomenal Principle can there be other than the presupposition that we always immediately perceive things other than real objects out in the world?

Hallucination

The argument from hallucination is more persuasive than the argument from perspectival variation, because it avoids any confusions regarding perceptual constancy. A direct realist can question whether or not the table does appear to be shrinking, but cannot so easily question whether hallucinations can be subjectively indistinguishable from episodes of perception. Objections have been raised to subjective indistinguishability, but this seems to me even more of a side-issue than perceptual constancy, so I won’t be pursuing it, at least not in this article. I want to accept subjective indistinguishability, not only because it is intuitively plausible, but also because in doing so we can go on to reveal more fundamental problems in the argument.

A.J. Ayer’s presentation of The Argument is possibly the most famous. In The Foundations of Empirical Knowledge he sets out the argument from hallucination as follows.

Even in the case where what we see is not the real quality of a material thing, it is supposed that we are still seeing something; and that it is convenient to give this a name. And it is for this purpose that philosophers have recourse to the term “sense-datum”. By using it they are able to give what seems to them a satisfactory answer to the question: What is the object of which we are directly aware, in perception, if it is not part of any material thing? Thus, when a man sees a mirage in the desert, he is not thereby perceiving any material thing; for the oasis which he thinks he is perceiving does not exist. At the same time, it is argued, his experience is not an experience of nothing; it has a definite content. Accordingly, it is said that he is experiencing sense-data, which are similar in character to what he would be experiencing if he were seeing a real oasis, but are delusive in the sense that the material thing which they appear to present is not actually there[8].

We can reconstruct the argument for convenience:

- P1. There appears to be something on the horizon which is an oasis

- P2. There is no thing on the horizon which is an oasis; it is just a mirage

- P3. If there sensibly appears to a subject to be something which possesses a particular sensible quality then there is something of which the subject is aware which does possess that sensible quality

- C1. Therefore when it seems that there is something on the horizon which is an oasis, there is no oasis which is the object of perception

- C2. Therefore the object of perception is a mirage, which is thereby a mental object

- P4. There is no way to tell whether or not we are hallucinating

- C3. Therefore the objects of perception in all cases are mental objects

It will be seen that this fits well into the general form, and the same criticisms apply. Ayer makes the false step very clear. Granted that “his experience is not an experience of nothing”, but to have an experience of in the case of hallucination is not to have an experience of an object, of a thing towards which experience is directed. “Experience of” an hallucination is logically equivalent to the above sense (2) of the word “see”, whereas “experience of” a real oasis is sense (1), meaning to perceive.

To ask “What is the object of which we are directly aware, in perception, if it is not part of any material thing?” is already to go wrong; an hallucination is not an object, and it is not perception.

The Causal Argument From Hallucination

To do more justice to indirect realism I must consider a version of The Argument which on the face of it does not fit in my general template and seems much stronger than any other versions: Howard Robinson’s “revised causal argument” from hallucination.

It is theoretically possible by activating some brain process which is involved in a particular type of perception to cause an hallucination which exactly resembles that perception in its subjective character.

It is necessary to give the same account of both hallucinating and perceptual experience when they have the same neural cause. Thus, it is not, for example, plausible to say that the hallucinatory experience involves a mental image or sense-datum, but that the perception does not, if the two have the same proximate — that is, neural — cause.

These two propositions together entail that perceptual processes in the brain produce some object of awareness which cannot be identified with any feature of the external world — that is, they produce a sense-datum[9].

The clue to unravelling this argument is the phrase “object of awareness” in the conclusion. Where does Robinson get it from? Well, he is explicit in taking the second premise to imply mental images or sense-data in both hallucination and perception. To bring out the mistake here it will be useful to look once again at the distinction I have already made between two ways of using the word “see”. Here I am going to make use of Audre Jean Brokes’ terms and label these uses as (1) perceptual visual experience, and (2) ostensible perceptual experience. (1) is seeing external things, and (2) is “seeing” mental images. Incidentally, I use scare quotes for the second usage because in a discussion about perception, seeing external things naturally ought to be the privileged usage, of which the second is derivative. [10]

It is only when Robinson implicitly and unknowingly privileges sense (2) that he can take it to apply to perception. In other words, to say that “hallucinatory experience involves a mental image or sense-datum” is not necessarily to say that the neural cause produces an object of awareness equivalent to an object of perception, because it remains much easier to account for these experiences by saying that what the neural cause causes is the experience itself. The hallucination constitutes the awareness, rather than being an object of awareness. In everyday life and by analogy with perception we might often use sense (2) to describe hallucination, saying things such as “I saw a dancing chicken, but it turned out it was just an hallucination”. But we cannot conclude from this that the dancing chicken was an object of awareness without taking “see” here to be used in something like sense (1), i.e., by taking the analogy literally.

In his conclusion it becomes obvious just what these ambiguities are leading to: an “object of awareness” in both cases. To make the argument valid, an extra premise is required, namely that hallucinations involve immediate objects of awareness. We are back to the Phenomenal Principle.

In Conclusion

Demolition is easier than construction: it still remains to give a positive account of perception. To that end, there are many questions to answer.

First, are we any further forward in answering the “problem of perception”, which is the need for an account of subjective indistinguishability? Is there even such a problem?

Is it accurate to talk about “objects of perception”? Do we not need a more holistic approach? After all, can it be right to say that in using our senses of smell and hearing we are acquainted, whether directly or indirectly, with objects of smell or objects of hearing? Even if it does make sense, are these objects the same as the objects of vision? To what extent are we justified in taking vision as primary? Obviously blind people cannot be excluded from these considerations, otherwise we are just doing something like empirical psychology. Or maybe these are just psychological questions?

And what is an object anyway? Is it something entirely independent of minds, or is it constituted by our particular way of individuating? So we come to the question: how realist can our realism really be?

I do not know. Whatever the answers, the weakness of The Argument suggests that we need to place it in a historical context so as to properly understand its meaning. We need to ask why it was so persuasive in the eighteenth century, and why, despite the best efforts of twentieth century philosophers, it remains persuasive, or even presupposed, in today’s culture.

We need to ask why many of the best thinkers in psychology, neuroscience and cognitive science are still so tied to the centuries-old idea that we live out our lives behind a veil of perception, one step removed from the world.

See the discussion about this article on The Philosophy Forum.

Footnotes

- [1] Hume, Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, Section XII

- [2] Robinson, H., 1994: Perception, London: Routledge

- [3] Austin, J. L., 1962: Sense and Sensibilia, Oxford University Press, p. 30

- [4] Russell, B., 1912: The Problems of Philosophy, Oxford University Press, p. 3

- [5] Image from Prof David Heeger’s lecture notes, online here

- [6] Heidegger, Martin, 1993: “The Origin of The Work of Art”, Basic Writings, quoted in A. D. Smith, 2003: Husserl and the Cartesian Meditations, Routledge, p. 83

- [7] Robinson, op. cit., p. 56-7

- [8] Ayer, Alfred J., 1953: The Foundations of Empirical Knowledge, McMillan, p. 3

- [9] Robinson, op. cit., p. 151

- [10] Brokes, Audre Jean, 2000: “The Argument From Illusion Reconsidered”, Disputatio 9 (1)

References

- Chemero, Anthony, 2009: Radical Embodied Cognitive Science, MIT Press

- Huemer, Michael, “Sense-Data”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL

- Johnston M., “The Obscure Object of Hallucination”, Philosophical Studies 2004;120:113-83

- Martin, Michael G. F. (2000). Beyond dispute: Sense-data, intentionality, and the mind-body problem. In Tim Crane & Sarah A. Patterson (eds.), The History of the Mind-Body Problem. Routledge

- Michaels, Claire F. and Carello, Claudia, 1981: Direct Perception, Prentice-Hall, PDF here