Tokyo Express and Some Other Novels by Seichō Matsumoto

I read three novels by Seichō Matsumoto: Tokyo Express (previously translated literally as Points and Lines) (1958); Point Zero (1959); and Inspector Imanishi Investigates (1961).

Except for Raymond Chandler, I’m not really into crime fiction, so I probably wouldn’t have read these books were it not for (a) my habit, when I have the opportunity, of browsing second-hand bookshops, thus exposing myself to happy accidents; and (b) my tendency to judge a book by its cover. I found Tokyo Express in a charity bookshop and was seduced by the beautiful Penguin Modern Classics livery, cover art, and quality typography. (I bought the others as e-books)

SPOILERS lie ahead. In summary, I think these books are very good. They are well-written, engrossing, ingenious, and humane. And, for those like me who are unfamiliar with Japanese culture, particularly that of the 1950s, they open up a new and fascinating world.

Tokyo Express

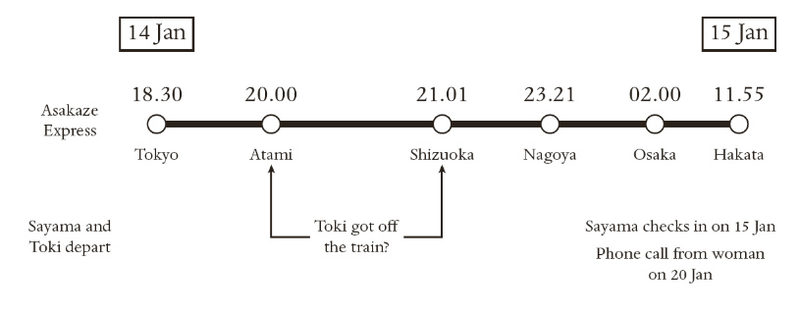

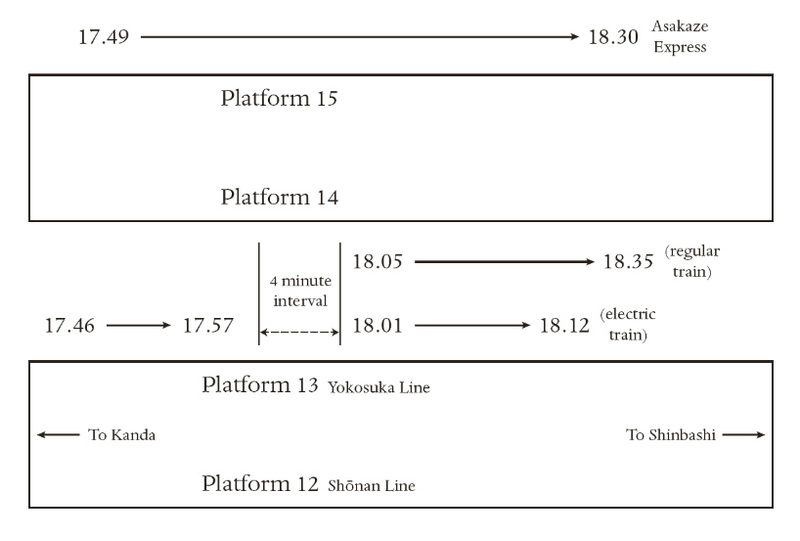

Some say you should avoid any novel with a map at the beginning. Tokyo Express not only has a map at the beginning, but also has a more detailed map within, as well as two diagrams, and various lists and notes representing extracts from the detectives’ notebooks. I might have struggled without all this — I was pitifully ignorant of Japan’s geography, for example — but more to the point, they make the book more attractive and intriguing, and they enrich the experience of reading it. The map naysayers are foolish snobs.

Tokyo Express, like the other two, is more of a howdunnit than a whodunnit. The stakes are low, and the atmosphere is cosy. All three are compelling page-turners, but they’re not manipulative thrillers that make you fear for the protagonist or their loved ones or make you expect one thing and then hit you with something else. They’re more like puzzles to be solved in a joint effort by the detectives, the reader, and the author. Tokyo Express is the purest of the three: a seemingly impossible crime, the facts of the case and every stage of the investigation laid out clearly and explicitly, the criminal drama relegated to a gradually revealed past — because the drama that really matters to the reading experience is just the solving of the puzzle.

Trains are prominent in all three novels, but in Tokyo Express they are central to the puzzle. This is a book for train-lovers, more especially the lovers of train timetables. It even contains a long quotation from a fictitious literary essay about the meaning and aesthetic wonder of train timetables. This is not an instance of maximalist self-indulgence (not that there’s anything wrong with that) but is actually important to the plot. However, there is more to it than that: one suspects that Matsumoto is sneaking in his own transit psychogeography, a pathos of passage, which perhaps even reveals the backstory of the novel’s creation:

At the very moment that I lie in bed […] trains are simultaneously coming to a halt all across the country. Countless people are getting on and off them, each following the course of their own life. I close my eyes and imagine these scenes. I am even able to work out, for each line, the stations at which trains are passing each other at that particular moment. This brings me great pleasure. The crossing of the trains is inevitable in time, but the meeting of their passengers in space is entirely accidental. I can fantasize endlessly about the lives led by all these people who, in faraway places, are brushing past each other at this very moment. I derive far more enjoyment from these flights of fancy than from any novel produced by someone else’s imagination. Mine is the solitary, wandering pleasure of dreams.

Yes — these days, the railway timetable, with its dense rows of numbers and unfamiliar names, has become my favourite reading material.

The novel’s single-minded dedication to the details of railway timetables, and more generally to the interlocking structures of human action across space and time — this borders on being unhinged and surreal, and it’s part of the pleasure.

In common with the other two novels, however, Tokyo Express is a bit more than a cosy abstract puzzle, and it would be an injustice to apply the label of “humdrum mystery”. Matsumoto is regarded in Japan as a pioneer of shakai-ha suiri, or “society-conscious mysteries.” We see this in Tokyo Express, which is rooted in the social reality of corruption and inequality, reflecting Seichō Matsumoto’s critical, leftish liberal attitude to the postwar establishment in Japan. Sayama, the prime target of the crime, is a government bureaucrat, but his rank is quite low and he seems to be mostly uninvolved in the corruption, such that, to the senior civil servants and ministers, he represents the risk of exposure. Both he and the other victim, a waitress, are young and innocent, which seems important given the author’s alignment with the significantly student-led protests against the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty in the 1950s, when the book was written.

I’m not interested in the obvious criticisms of this novel: undeveloped characters, stilted dialogue, a lack of surprises, and low stakes. These deficiencies are actually essential to the kind of book it is and what makes it a great example of this kind. Rather, my criticisms are about the puzzle itself, which is puzzling in a couple of ways it probably wasn’t meant to be.

The first is so glaring a problem that I’m pretty sure I just wasn’t paying attention, in which case I’m not going to call it a plot hole: how could the bad guy know that the couple would get on the train within the four minute interval, since it was going to be waiting at the platform for another 29 minutes? The answer is probably that he instructed them exactly when to arrive, but I didn’t find this explained satisfactorily. Everything else in the novel is explicit — Matsumoto always makes sure you know exactly where the investigation is up to, sometimes even repeating important information — so leaving this point implicit is so incongruous that it didn’t sit well with me.

The second problem is that the detective’s big breakthrough is too obvious: the bad guy travelled by plane instead of train. I had already thought of this before it was revealed, but because it hadn’t occurred to the detectives — or, apparently, to the author — I dismissed the idea, thinking it must be anachronistic.

That it didn’t occur to the police during several weeks of investigation stretches credulity, but on reflection I think it’s forgivable. In fact, it could even be realistic. Air travel was new at the time, and too expensive for the vast majority of people; it was probably not part of the Japanese consciousness in anything like the way that rail travel was. And tunnel vision is a common human failing: since the perpetrator had planned things so carefully, he succeeded in making the investigation focus on rail travel, and it’s natural that it would take the detectives a long time to realize how deep the deception went.

Point Zero

Point Zero is different from the other two in that it has a female main character, and one who is not a detective. This is important thematically, but plotwise she functions effectively as a detective: she is the point of view character and the one who solves the puzzle, and it is her thoughts that guide us step-by-step through the investigation towards the truth.

Matsumoto in all three of these novels has something like a formula. There’s (a) a seemingly impossible crime-puzzle, interwoven with (b) a context that emphasizes certain aspects of life and society in 1950s Japan. In Tokyo Express the social context is corruption in government, but in Point Zero it’s the struggles of women. The main character Teiko is a woman whose new husband — who she hardly knows, since the marriage was set up in the tradition of omiai, thus a kind of semi-arranged marriage — has disappeared. In investigating the disappearance, she uncovers a series of crimes relating to the experiences of the women who hung around with American soldiers after the war, dressing and behaving in the Western mode. In common with the other novels, then, the book tackles an aspect of the trauma of the Second World War and the occupation, in which Western and Japanese values and traditions came into conflict, and people had to come to terms with change. When a strictly hierarchical society, bound by deep traditions, is turned upside down, the effects linger on — and this is the reality that Matsumoto explores in all three of these books.

So in this case the murderer, a woman desperate to hide her shameful past, is treated very sympathetically by the author. We are no longer able to feel this as biting or shocking, but one can imagine that in 1950s Japan it was a daring choice of subject-matter, one rarely discussed in respectable circles. Matsumoto was too sensitive an artist to be an ideologue, but his work may have been quietly radical.

Inspector Imanishi Investigates

Inspector Imanishi Investigates is longer and more ambitious. I didn’t find this entirely convincing: I found a couple of the plot points confusing, had some difficulty keeping characters distinct in my mind, and began skipping over paragraphs towards the end — something I associate with trashy airport thrillers.

But it’s not entirely unconvincing either. One aspect of the novel’s ambition is the deeper development of the main character. We get to know Imanishi much more than we do with the characters in the other novels. We learn about his habits, his hobbies, his home life, and what he likes to eat — and we grow to like him.

It’s because he’s likeable that I was disappointed when he turned out to be disrespectful and mean-spirited with his wife and sister. This seemed out of character, but probably only because I had conveniently forgotten the taken-for-granted secondary status of women in that society. And it’s important to see that we are not necessarily meant to identify completely with him anyway. This is clear from the fact that the author himself doesn’t identify with him: Matsumoto has a lot of affection for Imanishi, but there’s a distance separating them. Imanishi, though a good detective, is much more unsophistocated, and much more ignorant of and uninterested in science and the arts, than Matsumoto. Whereas Philip Marlowe is a sort of idealized, and in his own way heroic, version of Raymond Chandler — the man that Chandler hopes he would be in Marlowe’s circumstances — the Imanishi character is a sympathetic study of a certain kind of Japanese man, one very different from the author.

So my point is that Imanishi’s patriarchal sexism is probably another aspect of this distance between character and author, meaning we can judge Matsumoto himself as innocent of this charge, and as maintaining his liberal credentials. I’m not just being woke here, but trying to work out how to interpret what Matsumoto is doing. (If in fact he does endorse the everyday sexism — quite doubtful given the themes of Point Zero, written not long before — his work remains interesting.)

By far the most ambitious formal novelty is the expansion of the point of view. There are chapters in which Imanishi is abandoned and we follow members of the Nouveau Group, a high-profile band of young intellectuals, writers, and artists, eager to play their part in the modernization of Japan. These young men are portrayed mostly as arrogant, spoiled brats, loudly proclaiming their righteousness while mistreating the people around them — particularly women.

From chapters following this educated urban elite, we follow Imanishi as he travels into the poor hinterland, and here Matsumoto hits us with a picture of poverty that, unlike a lot of the social commentary in these books, still has the power to shock. And whereas Tokyo Express and Point Zero address the occupation and in general the aftermath of the war, Inspector Imanishi Investigates tackles the war more directly, describing the firebombing of Tokyo and the upheaval of communities that it caused. What is impressive is that Matsumoto weaves these things into the plot, so that they’re far from forming a mere backdrop to action.

Conclusion

I liked these books very much. Tokyo Express might be my favourite, but I can’t deny that the later two novels were more affecting, because they more thoroughly complexified the crime-puzzles with social and cultural commentary that gave me a deeper appreciation of the diverse effects on Japanese society of the war and the U.S. occupation.

Underlying that social rootedness there is a geographical specificity to everything that happens; the poetics of place is ever-present. Matsumoto’s characters travel all over the country, and each of these visits has its own atmosphere and mood conditioned not only by the thoughts and feelings of the point-of-view character but also by the landscape, the season, and the weather, rendered efficiently in a few brush strokes.

The novels are quick, light, and fun, but also specific to time, place, and community, and haunted by the Second World War and by the disappearing traditions of old Japan. Recommended.