The Republic by Plato, Part 1: Book 1

Plato, Republic, translated by C. D. C. Reeve, Hackett (2004)

When I picked up the Republic recently I read it as superficially as I did when I read it for the first time twenty years ago. Despite a few slow spots, and despite how infuriating it can be, it’s a page turner, and that kind of reading is not conducive to philosophical reflection. Julia Annas, in her Introduction to Plato’s Republic, says that the Republic is too famous for its own good; I think it’s also too well written for its own good. You can read it like any other dramatic narrative, whereas if you read, say, Aristotle, Kant or Hegel, you are necessarily studying Aristotle, Kant or Hegel.

But this time I was self-aware enough to see what was happening, so my approach turned out to be as follows:

- Read the Republic.

- Read some secondary literature, primarily Julia Annas’s book, which, more than merely an introduction, is a thorough and opinionated analysis based on decades of studying and teaching the Republic.

- Read the Republic again, while summarizing it and making notes in the form of these blog articles, consulting secondary literature as I go. This is where I’m at now.

I recommend this strategy to newcomers (leading or taking part in a reading group would make it even better). The essential things, in my opinion, are to read the Republic closely and repeatedly, and also to use secondary literature, because the distance separating us from Plato is such that we need to learn from those possessing a deep understanding of the period, of the philosophical context, and of the rest of Plato’s work. Without this help it is too easy to dismiss Socrates’ arguments and to reject his repellent proposals, whether the destruction of the family or the censorship of the arts.

Among the video lectures I’ve found, the series that’s both engaging and reliable is Jonathan Culp’s 11-part Introduction to the Republic on YouTube.

What is the Republic about?

This is a question for later, but it’s worth bearing in mind. Is it only concerned with justice or is there more to it? Is Kallipolis, Plato’s ideal city, a serious proposal? Is it rather aimed at uncovering the structure of the soul and what it means to be a just person? Or is the book about philosophy itself? Is it primarily a demonstration and invitation to philosophy and dialectic? If it’s a combination of all these, what is the balance, and is there a primary thrust?

Plato or Socrates?

Most of the time I take it for granted that Socrates is Plato’s mouthpiece. He is a character, but he is the special character through which Plato demonstrates what doing philosophy is about, describes the end to which dialectic aims (knowledge of the Forms and especially the Form of the Good) and through which he sometimes lays out his actual positions on various subjects, particularly in the Republic. The upshot is that I might often use “Plato” and “Socrates” interchangeably. This might not be the whole story, and there does remain a question as to how much Plato agrees with Socrates, but for convenience and in line with most interpreters I’ll assume that Plato is expressing himself through Socrates.

Terminology

Justice: The best translation of Plato’s dikaiosune, but note: the modern notion of justice involving equality before the law, individual rights, and obeying the law, is not quite the notion he was working with. Plato’s justice is a virtue; it’s a matter of personal character, and he is concerned most of all with its impact on the well-being of the community as a whole. And while obeying the law might be required for Plato’s justice, there’s a lot more to it. So Plato’s version is more expansive, encompassing all kinds of right conduct in personal interactions that nowadays we might be more likely to think of as a matter of morality.

Morality: So I’ll probably be using the term moral quite a lot, when I need to emphasize the expansive meaning of dikaiosune. But the morality I’m talking about here is always general: it’s about practical reasoning and the right way to live, not about good versus evil or properly moral versus merely prudent acts and reasons — notions that are alien to Plato.

Elenchus: The Socratic method of philosophical investigation, Plato’s favoured form of dialectic, in which Socrates questions someone’s beliefs until contradictions emerge. It is really only used in Book 1; thereafter, Socrates’s interlocutors don’t do much interlocuting and mostly just agree with everything he says. (This makes the Republic a much more dogmatic work than the earlier “What is X?” dialogues, in which the elenchus was the central method).

City: The polis, meaning a city state, which I’ll usually just translate as the city even though it implies more than that term usually does for us: a polis is basically a small sovereign country comprised of an urban settlement, the surrounding farmlands, and often a port.

Republic: The original title is Politeia, which refers to the constitution, the community, and the way of life of a polis.

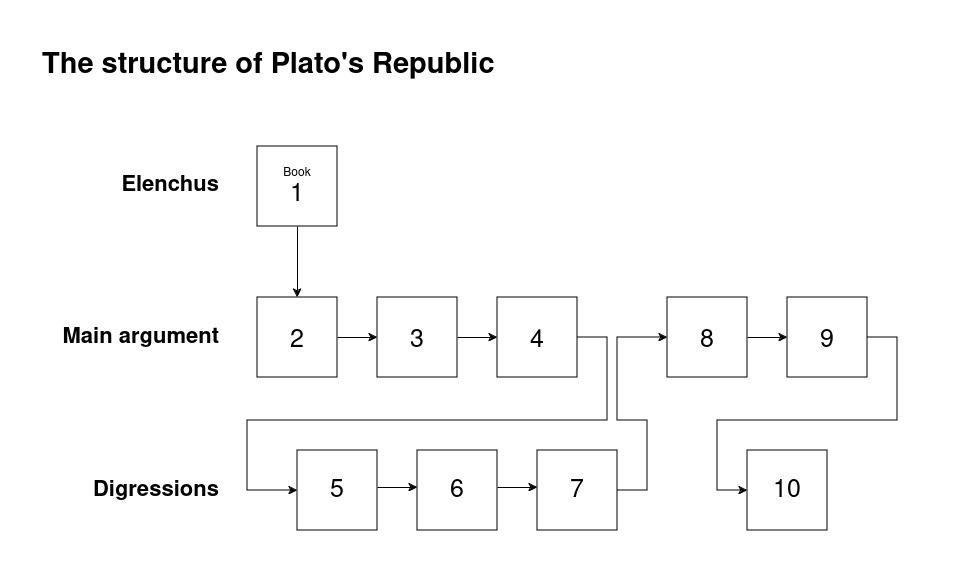

The structure of the work

Based on https://www.slideserve.com/Ava/plato-s-republic

Based on https://www.slideserve.com/Ava/plato-s-republic

Book 1: Dramatic setup and Socratic elenchus, eliciting the central questions that the rest of the book will answer: (1) what is justice? and (2) is the just life happier than the unjust life?

Books 2-4: The first part of the main argument. Justice in the city as a model for justice in the individual, leading to the thought experiment of building the ideal city in speech, leading to an answer to question (1).

Books 5-7: More detail about how the ideal city will work to answer objections to its practicality and desirability; and within this we get the heart of Plato’s theoretical philosophy, i.e., his metaphysics and epistemology.

Books 8-9: The second part of the main argument, answering question (2).

Book 10: The banishment of the poets and the Myth of Er. A crude excrescence or a dumbed-down summary?

Philosophy as dialogue

Although the Republic is much more dogmatic than Plato’s earlier dialogues (where dogmatic here means relating to positive doctrine; offering actual theories and positions rather than just questioning beliefs) it is still framed as a dialogue and kicks off with the elenchus. So even though Plato goes on to tell us at length through Socrates what he really thinks, we often feel like joining in to offer better questions and criticisms than his interlocutors manage, and it is the dialogue form that encourages this. This is by design: for Plato, dialogue, a form of dialectic, is the basic stuff of philosophy.

On the other hand, a less positive way of seeing this is that for Plato dialogue exhibits mere belief as opposed to knowledge, such that dialogue is ultimately inferior, or at least an incomplete beginning, from the point of view of the philosopher. Hence his move to the exposition of doctrine. In Book 1 and the earlier dialogues, Socrates is down in the dirt, questioning people’s beliefs — whereas what might ultimately be needed is to inspire people with something approaching the truth, something positive.

And there certainly is a disconnect between Book 1 and the rest of the Republic. This has led some people to suggest that Book 1 was written separately, but to me it’s just an admission by Plato that the questions that come up there require a lengthy and expository mode to answer properly. Dialogue is basic, but some things take a while to explain.

But this apparent disconnect allows us to see that Plato is a subtle, dialectical thinker, in something like the modern Hegelian sense. The interdependence of opposites is important: between dialogue and dogmatism, practical and contemplative, up and down (see below), reality and mere images, seeing the light and returning to the cave. So Plato is not, or is not merely, denigrating one and glorifying the other. I think this is crucial to bear in mind throughout the Republic.

It is in this dialectic as it is here understood, that is, in the grasping of opposites in their unity or of the positive in the negative, that speculative thought consists.

— Hegel, The Science of Logic

Book 1

Book 1 ultimately poses the two central questions that the main argument of the Republic attempts to answer:

(1) What is justice?

(2) Is the just life more personally beneficial than the unjust life? Or, is the just life happier than the unjust life?

Following the opening dramatic framing, Socrates’s elenchus proceeds through various interlocutors until it fails to properly answer the last of these, Thrasymachus, whereupon the two central questions remain up in the air, unanswered to anyone’s satisfaction.

Question (1) appears early in Book 1, and question (2) arises by implication from the position of Thrasymachus, who says that justice is that which is in the interests of others, that in fact, it is injustice which is in one’s own interest and which thus brings happiness.

What is justice?

Pausing from the exegesis here, we can ask ourselves this question. Personally I found it quite difficult to come up with a good answer. I suppose I’ve always thought of it as a sort of codified fairness: giving to people what they deserve, respecting people’s rights, and ensuring the equitable distribution of wealth and freedom. We’ll see that this is partly similar and partly very different from the notions of justice that appear in the Republic.

Literary excellence

I’ll be focusing mainly on the philosophy and the arguments, but it’s worth looking at the Republic as a work of literature. Book 1 is where this matters most of all.

The Republic is narrated by Socrates, and he begins by describing the circumstances of the discussion that takes up the whole work. This gives us the work’s dramatic frame, even though it is not referred to again after Book 1.

It’s easy to skate over this stuff, but many commentators have seen more than is apparent on the surface. Take the very first line:

I went down to the Piraeus yesterday with Glaucon, the son of Ariston, to say a prayer to the goddess …

[327a]

According to many interpreters, the idea of going down relates to the important dichotomy between up and down in the cave allegory and elsewhere in the Republic:

| UP | DOWN |

|---|---|

| Light | Shadow |

| Reality | Illusion |

| Rational | Irrational |

| Intelligible | Sensible |

| Knowledge | Opinion |

| The absolutely good | Qualified goods (contingently good things) |

| Being | Becoming |

| The Forms | Particular instances, and imitations |

But note: many of these are connected and overlap, and more importantly, there are gradations between up and down that are made explicit in the Republic, so there is continuity, not merely strict dualism. And my point above about dialectical thinking is obviously relevant here.

When Socrates says he went down, he might be implying that he went down among those — his interlocutors — who have not attained knowledge, those whose souls are not ruled by reason, and who are, say, imperfectly virtuous. More positively, Plato could be stressing that one must go “down” to ordinary life to see how philosophy can help, that philosophy is not only theoretical but must also be practical. This mirrors the cave allegory, in which those who have seen the light are persuaded to go back down into the cave and apply their knowledge to ordinary life.

Others have pointed out the significance of having Socrates going to say a prayer to the goddess. Plato was writing in the years following the execution of Socrates in 399 BCE, partly for impiety, something that all his readers would be aware of. Thus Plato subtly defends his mentor against the democratic polis.

My first reaction to these literary interpretations was scepticism, because I had not detected any subtext at all. But I have come around to agreeing. Plato was a sophisticated and careful literary artist, and a really smart guy: there is intention and significance in everything he writes, not least in his frame narratives and first lines (which were as significant then as they remain today).

Next, in the banter between Polemarchus and Socrates there is some allusion to the Republic’s themes:

POLEMARCHUS: It looks to me, Socrates, as if you two are hurrying to get away to town.

SOCRATES: That isn’t a bad guess.

POLEMARCHUS: But do you see how many we are?

SOCRATES: Certainly.

POLEMARCHUS: Well, then, either you must prove yourselves stronger than all these people or you will have to stay here.

SOCRATES: Isn’t there another alternative still: that we persuade you that you should let us go?

POLEMARCHUS: But could you persuade us, if we won’t listen?

GLAUCON: There is no way we could.

POLEMARCHUS: Well, we won’t listen; you had better make up your mind to that.

[327c4]

According to Sean McAleer this centres on a pun on Socrates’ name, which contains cratos, meaning strength or power. Even so, it functions as foreshadowing, introducing some of the Republic’s political and philosophical themes: power vs wisdom, persuasion by argument vs compulsion by force, rational vs irrational.

At this point Adeimantus and Polemarchus chip in with the promise of sensory excitements:

ADEIMANTUS: You mean to say you don’t know that there is to be a torch race on horseback for the goddess tonight?

SOCRATES: On horseback? That is something new. Are they going to race on horseback and hand the torches on in relays, or what?

POLEMARCHUS: In relays. And, besides, there will be an all-night celebration that will be worth seeing. We will get up after dinner and go to see the festivities. We will meet lots of young men there and have a discussion. So stay and do as we ask.

GLAUCON: It looks as if we will have to stay.

SOCRATES: If you think so, we must.

[328a]

This could be seen as deepening the political allegory: the powerful sometimes buy the compliance of the people with entertainment (and in this case discussion, which is Socrates’ favourite activity). And Socrates finally gives in, not simply under the (playful) threat of force and the enticements of the senses but also under the pressure of a democratic decision.

Cephalus

Cephalus, the head of the household and father of Polemarchus, is a wealthy merchant and resident alien, living in the Piraeus like all other resident aliens (we know this from other sources, since along with the other characters he was a real person, and a prominent one).

He was sitting on a sort of chair with cushions and had a wreath on his head, as he had been offering a sacrifice in the courtyard.

[328b8]

Sacrifices are mentioned a few times in the early part of Book 1: Cephalus has been doing it prior to the group’s arrival and will do it again when he departs from the discussion. Thus he is portrayed as conventionally pious.

He greets Socrates warmly, and goes on to say:

I want you to know, you see, that in my case at least, as the other pleasures — the bodily ones — wither away, my appetites for discussions and their pleasures grow stronger.

[328d]

It’s fun to read this as Annas does, namely as a back-handed compliment which is likely unintentional but which Socrates would certainly notice: Cephalus implies that philosophy is for old people with nothing better to do. Plato is beginning his characterization of Cephalus as someone who is moral and just in an unthinking, complacent and conventional way.

That said, Socrates seems quite sympathetic and affectionate. At least on the surface, he doesn’t hold Cephalus in contempt (as some interpreters suggest) but rather sees him as normal, i.e., as ordinarily unenlightened, such that he can be used to represent the weakness of traditional authority and of conventional, common sense attitudes to justice — the weakness that allows relativism and nihilism to get a foothold, as represented later on by the sophist Thrasymachus.

Following some discussion about wealth and old age, Socrates asks the question [330d], “What do you think is the greatest good you have enjoyed as a result of being very wealthy?” Cephalus answers that wealth allows you to be just when your end is near and you begin to worry about the afterlife — but only if you already have a good character. And being just and pious for him is paying people what you owe, making sacrifices, and telling the truth — a list of duties.

This is the first mention of justice in the Republic, and this is what Socrates is interested in, so he extracts from Cephalus’ words a definition of justice, and asks if it’s right:

SOCRATES: But speaking of that thing itself, justice, are we to say it is simply speaking the truth and paying whatever debts one has incurred?

[331c]

He goes on to show that it cannot be right: if you borrow a sword from your friend, and then the friend goes insane, it can’t be just to give it back, even though you owe it to him, because in his insane state he could cause harm with it; and it can’t be just to always tell the truth to such a person, e.g., if he asks for the whereabouts of your father, whom he has insanely decided is his mortal enemy. Therefore justice cannot be giving back what you owe and telling the truth.

Cephalus’ son Polemarchus joins in here to defend the definition, and Cephalus jumps on the chance to leave. Despite his express wish to engage in more discussion in his old age, he isn’t really up for it, and departs to attend to more sacrifices. Since he was making sacrifices only a short while before, we might suspect this is just an excuse; either way, Plato is getting his point across: Cephalus is either traditionally pious out of fear of punishment in the afterlife, or he is unwilling to think, to submit his own beliefs to intellectual scrutiny — or both. He has been a good man in everyday life, but for Plato that’s not quite enough.

Verbal vs Real definitions

As Julia Annas points out, talk of definitions here can be misleading. Socrates is not interested in words as such, but about things themselves, and probably doesn’t see the importance of distinguishing between the two. Certainly, he is not interested in how the word “justice” is commonly used, but wants to get at the thing itself, that which lies behind our common intuitions. If his aim is to find a definition it’s to find what is sometimes called a real definition, rather than a verbal one: a description of the nature of the thing rather than a description of the word’s signification.

Polemarchus

Polemarchus begins with an appeal to authority, that of the poet Simonides, who said that justice is giving to each what is owed to him (telling the truth is dropped here). Socrates reminds Polemarchus of his earlier refutation, and Polemarchus clarifies what Simonides meant: justice is giving to each what is appropriate to them, namely good to friends and bad/harm to enemies.

Socrates here proceeds by elenchus under the assumption that justice is a craft, comparable to other crafts such as shoemaking, farming, and captaining a ship. He ties Polemarchus in knots by arguing that according to the current definition, justice is (i) not something excellent, i.e., it is something trivial; and (ii) justice is a craft of theft that benefits friends and harms enemies. Polemarchus, understandably, is not comfortable with these conclusions. Finally (iii) Socrates argues that justice cannot allow doing harm to anyone, including enemies.

Thus the definition that Polemarchus offers has been shown to be wrong.

Argument (i) [332a-333e]

In the various activities of life one applies the special skills of a craft or employs someone else who has those skills, but the craft of justice turns out to have no field to apply itself to, since wherever you look, some other craft is more applicable, whether it’s making money, captaining a ship, or playing the lyre. Justice then is only useful when the instruments of one’s activity — money, ships, and lyres — are not in use:

SOCRATES: And so in all other cases, too, justice is useless when they are in use, but useful when they are not?

POLEMARCHUS: It looks that way.

SOCRATES: Then justice cannot be something excellent, can it, my friend, if it is only useful for useless things.

[333d10]

We get the feeling that Socrates has tricked Polemarchus, and the argument is not immediately convincing. Even if we grant the doubtful premise that justice is a craft, Polemarchus could surely say that one can exercise the skill of justice while at the same time exercising more specialist skills, that is, justice is a higher level craft that encompasses all others.

But Socrates is examining Polemarchus’ beliefs. That Polemarchus does not offer the above objection and nods along with Socrates suggests that he thinks of justice as just another skill, applied instrumentally as a means to an end — but where that end, if it can be identified, is trivial. Thus Socrates assumed the premise in the first place because he suspected it was in line with Polemarchus’ notion of justice, and the ensuing arguments then amount to a series of reductio ad absurdums. In the present argument: Polemarchus may feel intuitively that justice isn’t trivial, but his limited conception of it implies that it is.

Annas suggests that the thrust here is to show that although justice can fairly be described as a skill — Socrates is not very much against this, even if it’s inadequate — we surely want to say that it is an important one, and Polemarchus’ conception cannot produce this conclusion because in actual fact justice is not all that important to him. Justice for him and his father is routine and easy. My possibly uncharitable view is that he is uncomfortable with this because of how it makes him look.

Socrates keeps going…

Argument (ii) [333e-334b]

Since justice is a skill alongside others, it shares a feature that they have, namely that it can be used to achieve the opposite of whatever it normally sets out to do; hence the skill of justice will sometimes be used to achieve the opposite of justice, just as the skills of medicine allow a doctor to easily make someone ill rather than making them better. Socrates in the end uses the example of theft: if justice sets out to guard money, it can also be used to steal it (so long as this is to benefit friends and harm enemies).

Again, it is open to Polemarchus to object that actually, justice is not the same as other skills: rather than an instrumental skill which is neutral as to its consequences, it is a virtue, so it necessarily always aims for a good end and cannot aim for its own opposite. And again Polemarchus doesn’t have the resources for this, for the same reason as before: justice is to him just another skill, with nothing all-encompassing about it.

Polemarchus feels he cannot agree with the conclusion that justice is a skill of theft, and cannot understand how the argument has led to it. Again, his concept of justice, as elucidated by Socrates, leads to a conclusion that he finds intuitively objectionable. But still, he wants to stick to the definition he originally gave, so Socrates goes in a different direction.

Socrates points out to him that people make mistakes about who among their friends is good and who is bad, which implies that it’s sometimes just to harm one’s friends, since some of one’s friends may be bad. This pushes Polemarchus into revising the definition of a friend: a friend is one who is both believed to be good and is in fact good.

SOCRATES: So you want us to add something to what we said before about the just man. Then we said that it is just to treat friends well and enemies badly. Now you want us to add to this: to treat a friend well, provided he is good, and to harm an enemy, provided he is bad?

POLEMARCHUS: Yes, that seems well put to me.

[335a6]

At this point, Socrates begins a new argument.

Argument (iii) [335b-e]

His question is:

SOCRATES: Should a just man really harm anyone whatsoever?

[335b2]

He argues that when you harm something, it becomes worse with respect to the virtue that makes it good, and since justice is the peculiarly human virtue, harming a person makes them worse in that respect, that is, more unjust. But justice, being a virtue or a goodness, cannot be used to make a person bad, so the purpose of justice cannot be to harm anyone. And Polemarchus gives in and agrees, abandoning his definition.

There is a translation issue here which reveals a fundamental difference between our concept of virtue and that of the ancient Greeks. Virtue for Plato and his contemporaries (their word is arete) is what is possessed by a thing — human, animal, or inanimate object — that enables it to do what it’s meant to do, i.e., that which enables a thing to perform its function well, where everything has its characteristic function. It is close to our notion of excellence. To say that a leopard is a good or excellent leopard is to say that it has the arete that a leopard must have to be a good or excellent leopard, e.g., that it is good at hunting antelope. To say that a knife is a good or excellent knife is to say that it has the arete that is specific to a knife, namely sharpness. And to say that a human is a good or excellent human is to say that it has the arete specific to a human, namely that it is just (among other virtues).

Today we think of virtue as exclusively a moral matter, in the stricter and more modern sense of moral — we probably think of saintliness and righteousness — but for the ancient Greeks there was no conceptual gulf between moral virtues and the virtues of leopards and knives; these virtues differ greatly among themselves but they are the same kind of feature, each one appropriate to the characteristic function of the thing it belongs to. Reading argument (iii) with this in mind shows it to be much more convincing than it initially appears. It’s also crucial to bear in mind more generally when reading the Republic that being virtuous and good is closer to excellence than it is to the goodness of Christianity (although there is a lot of overlap). Incidentally, following the long process of secularization that started with the Enlightenment, many people today, including myself, are in many ways closer to Plato than to the Christian conception of virtue, and it’s no coincidence that there has been a revival of virtue ethics, rooted in ancient Greek thought, since the mid-twentieth century.

But neither Socrates nor Plato are actually committed to the conclusion that the just person doesn’t cause harm to anyone. These arguments have been the elenchus aimed at exposing the inadequacy of common sense beliefs. So the point so far in Book 1 has been to show, in Celaphus’ complacency and avoidance of debate, and in Polemarchus’ confusion and incoherence, that the conventionally just person is content to check off a few conventional duties but has no rational basis for this.

But the fact remains that they are portrayed as basically virtuous, at least conventionally and in their everyday lives; and Socrates does want to preserve something of their views. Their definitions are in the right ballpark, even though they’re inadequate and incoherent: behind them lie intuitions that point to something greater, more important and more essential to justice than they are able to conceptualize. Their concept of justice implies things that they intuitively reject, and it is these intuitions which are right. The problem for Socrates is that so long as justice remains for a person an intuition rather than a rational conceptualization, it is not true justice — for that, knowledge is required. This will be developed explicitly by Plato later on.

Once Polemarchus has abandoned his definition, Socrates attributes it to various famous men to suggest that it originates not in the wisdom of poets like Simonides but in the biased and self-serving opinions of rulers and politicians with the money and power to destroy their political rivals:

SOCRATES: You and I will fight as partners, then, against anyone who tells us that Simonides, Bias, Pittacus, or any of our other wise and blessedly happy men said this.

[335e7]

SOCRATES: Do you know whose saying I think it is, that it is just to benefit friends and harm enemies?

POLEMARCHUS: Whose?

SOCRATES: I think it is a saying of Periander, or Perdiccas, or Xerxes, or Ismenias of Thebes, or some other wealthy man who thought he had great power.

[336a]

Socrates’ laudatory comments about Simonides seem ironic, but I struggled to understand in exactly what way. Thanks to a discussion I started on thephilosophyforum.com, Poets and tyrants in the Republic, Book I, things became a lot clearer, and I’ve set out my improved interpretation in this post. In a nutshell, Socrates’ praise of Simonides is an exaggeration or affectation, because he doesn’t really care what Simonides actually said or whether he was actually wise. Plato’s emphasis is on an understanding of the definition or saying which is independent of any authority.

Thrasymachus, who has been watching and listening the whole time, can’t contain himself any longer, and he steps up to the role of antagonist. I’ll be covering him in part 2.

Notes

- Plato, Republic, translated by C. D. C. Reeve, Hackett (2004)

- Julia Annas, An Introduction to Plato’s Republic, Oxford: Clarendon Press (1981)

- Sean McAleer, Plato’s Republic: An Introduction (Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2020), https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0229

- LeMoine, Rebecca, “Philosophy and the Foreigner in Plato’s Dialogues.” Ph.D. Diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison (2014)

- Futter, Dylan. (2021). SOCRATES ON POETRY AND THE WISDOM OF SIMONIDES. Akroterion. 65