Remembering the Future, Soviet-style

Moscow: A Guide to Soviet Modernist Architecture 1955–1991

By Anna Bronovitskaya

Finding this book was a pleasant surprise. I had come to think that the only period of modernist architecture in Moscow that was somewhat appreciated was constructivism, Russia’s influential contribution to the international modern movement of the 1920s. Although many of the remaining buildings are in disrepair, constructivism is increasingly celebrated in Russia. This is unfortunately not the case for the architecture of the 1960s and 1970s, which is why this book is so welcome.

As in Britain, postwar and particularly 1960s/70s modernist architecture in Russia is generally thought of as ugly, gloomy, technocratically imposed, hopelessly utopian, badly planned and executed, built on the destruction of beautiful old buildings, and so on.

And it can be all that, yet I love it. And now I’ve found a book about it, focused on where I currently live, which reminds me that I’m not just a perverse eccentric.

Gorky Art Theatre, © A.Savin, WikiCommons

Gorky Art Theatre, © A.Savin, WikiCommons

This book by Anna Bronovitskaya, published by the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, allowed me to see that architects in both East and West were bitten by the bug of utopian optimism, in ways and for reasons that were both similar and different. In the West, after the war it was time to rebuild, and this was seen as an opportunity not simply for some new buildings but rather for a new society, one based on rational and scientific principles for the benefit and improvement of the people. The barbarism of war could be put behind us by sweeping away the old, beginning again with new ways of living, which entailed not only new institutions, but also new kinds of buildings and new schemes of urban planning.

Thus in Britain we got the Welfare State and the NHS alongside ambitious plans for the reconstruction of British towns and cities. New Towns are a good example, as were the extensive redevelopments in the city centres of Glasgow and Birmingham, which replaced the old inner city slums with Corbusian housing schemes, tower blocks, pedestrian precincts, and shopping centres — all surrounded by new roads cutting through and sometimes over the old neighborhoods. It was happening in the outskirts too: due to the post-war housing crisis there was a massive push for the construction of new social housing, and this presented architects with the opportunity to experiment according to the principles of modernism, which had not by this time made much of an impact in Britain.

What I’ve learned from the book is that in Russia, a similar mood began to take hold after the war — only a bit later. It was not the end of the war but the death of Stalin in 1953 that marked the change. Stalin’s regime had been characterized by a conservative architectural style, imposed on all architects from above: under Stalin in the 1930s, the modernism of the 1920s was rejected, and the era of totalitarian Stalinist wedding cake architecture settled in for the next fifteen or twenty years.

When Stalin died and the rejection and condemnation of his policies became widespread in the Soviet Union — even if this de-Stalinization was not always widely publicized — architects were able to get back to their interrupted modernism, and as in the West it was associated with a hi-tech optimism and a humanist concern that had been absent until then. Architects and urban planners could help bring about true communism, which was always acknowledged to be a work in progress.

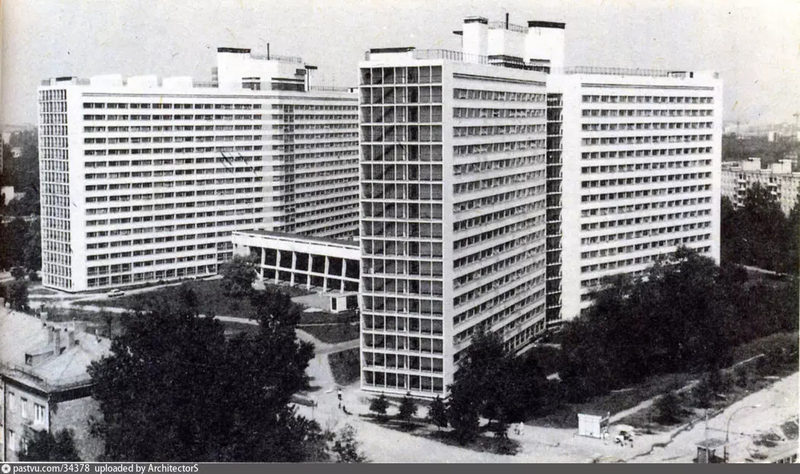

The House of New Life

The House of New Life

One of those architects was Nathan Osterman, who designed the House of New Life (Dom novogo byta), which is just around the corner from where I’m living as I write this. Sociologists were also involved in the design, and even prospective residents were consulted about it. The resulting plan would have produced an impressive provision of services for young families, to serve as a model for future communist housing.

Osterman’s project involved the construction of a residential complex with a fantastic range of services for that time. What’s even more unusual is that the potential residents of the House of New Life – young families – took part in compiling the list of these services. The result was an impressive list, which included a gym, a swimming pool, a children’s center, a winter garden, a film laboratory, reading rooms, a buffet-bar-billiards room and much more. Solariums and a dance floor were supposed to be on the flat roof.

In the end, most of that was deemed too expensive, and when Osterman died before it was completed in 1971, the building was transferred to Moscow State University for graduate student accommodation. And so it remains today, but despite the university’s prestige, the building has not been well-maintained, if the exterior is anything to go by.

So it wasn’t just a failure to realize the great experiment of communism, but more mundanely, a failure to see through a few ambitious architectural plans to completion. Many of the projects suffered from compromises and the resulting buildings were often too cheaply constructed, not fit for purpose, and unpopular.

That said, several modernist buildings from the period are doing pretty well, like the Gorky Art Theatre, the Great Moscow State Circus and the Ulitsa 1905 Goda Metro station (among several others).

Great Moscow State Circus, © A.Savin, WikiCommons

Great Moscow State Circus, © A.Savin, WikiCommons

Metro Ulitsa 1905 Goda

Metro Ulitsa 1905 Goda

And despite the problems, I still love the buildings of this era. Not only are many of them sculpturally beautiful, visually exciting and impressive, but they stand (for now) as a reminder of a more ambitious and optimistic time, when people believed they could shape the future in radically different ways, and when architecture had a social mission.

I tend to be sniffy about “ruin porn” and similar tendencies: the love of ugly, dilapidated, often modernist buildings precisely because they are ugly and dilapidated. It seems quite shallow and unimaginative, and just another facet of the popular association of post-war architecture with urban decay, which I want to resist, because I believe that the ideas of these architects really did represent a potential for better ways of living and working. But I have to confess that the sheer monumentality and intimidating quality of some of the buildings is a factor in my fascination.

Many of them are now at risk of demolition, and many have already been either demolished or literally defaced with advertising or panelling. One of the stated aims of the book is to help convince Muscovites that these buildings are worth preserving. I hope it succeeds.