CPR: Transcendental Aesthetic I

Definitions

See [B33-34]

NOTE: Out of curiosity I read a few pages of the beginning of the Transcendental Logic, which comes after the Aesthetic. [B74-76] is very useful for straightening out these definitions.

Aesthetic:

Of the senses

Objects:

So far I sense an ambiguity in Kant’s use of 'object’. Are we meant to think of objects of experience – this is the interpretation I’ve been favouring so far – or does he mean objects in themselves? Another alternative is that his use of object could be neutral/independent of this question. That is, objects under Kant’s doctrine are indeed of experience and not in themselves, but this is sometimes left up in the air. See the definition below for appearance.

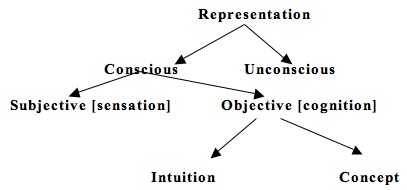

Representations or Presentations:

Objects as given to us, i.e., most important at this stage are two kinds of representation: intuitions and concepts. But also, it seems – and confusingly – sensations, perceptions and appearances. This indicates that “presentation” is a very general term for some sort of experiential element. But what is the difference between presentations and appearances. Well, I think appearances probably are presentations.

representations

See http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-spacetime/

Intuition:

Intuitions are representations concerning that which is given by the sensibility. They come in two types: empirical intuitions, which directly represent that which is given in sensations; and pure intuitions, which are the forms in which things are intuited. There are also representations that are not given to us through the sensibility, i.e., representations that are not intuitions: concepts. This works well with Schopenhauer’s use of the term — as I describe here. Intuitions are particular.

Sensibility:

Our receptivity to objects, such that we can have representations — and therefore intuitions. In other words, our capacity for having/making representations. Objects are given to us through the sensibility. It is that which produces intuitions.

Sensation:

The effect of objects on the sensibility.

Empirical intuition:

A direct representation given through sensation.

Pure intuition:

An intuition given through the pure form of sensibility, i.e., not a direct representation of appearances, but a representation which amounts to the form of intuition. Pure intuitions are apparent in the experience of objects, but are themselves not representations of objects. Space and time.

A priori sensibility:

The a priori forms of sensibility, the principles of which we should study through the science of transcendental aesthetic

Appearance:

The undetermined object of an empirical intuition [what does that mean?]

The Given:

Probably another, more general name for appearances. But I’m not quite sure.

Understanding:

The capacity for thinking objects, parallel to sensibility. That which produces concepts.

Concepts:

Representations of representations/intuitions. Second-order or indirect representations, rather than the direct representations that are intuitions. Alternatively, just the representations through which we think objects. Concepts are general.

NOTE: Notice here — in e.g., the definition for pure intuition — that the forms of experience, of sensibility, are not concepts, i.e., they are intuitional. We’re talking space and time here, of course.

Thus, if we separate from the representation of a body what the understanding thinks in regard to it, such as substance, force, divisibility, etc. [primary qualities], and likewise what belongs to sensation, such as impenetrability, hardness, colour, etc. [secondary qualities], there still remains something of this empirical intuition, namely extension and shape [primary qualities under Locke’s view but now viewed differently]. These belong to pure intuition, without an actual object of the senses or of sensation [what’s the difference? I’ll assume none] exists a priori in the mind, as a mere form of sensibiliy. [B35]

Things to Note About The Intuition/Concept Split

| Sensibility | Understanding |

| Receptivity | Spontaneity |

| Intuitions | Concepts |

Careful, though: intuitions are not the same as sensations. TODO: explain the difference

- Intuition and understanding are interdependent but separate

- It goes against both the rationalists and empiricists, both of whom conflate intuition and understanding in their own ways [B327]

Regarding 2…

Empiricists: Treat understanding as wholly a matter of sensation, i.e., sensible objects as the stuff of thought

Rationalists: Reduces empirical objects to indistinct concepts (clear & distinct vs obscure & indistinct ideas).

Space and Time

According to Kant, space and time are a priori intuitions.

Space and time also supply the missing ingredients in the synthesis of knowledge with regard to intuitions. Recall:

How then can I predicate of that which happens, as belonging to it, and belonging to it necessarily? What is here the unknown = X, on which the understanding relies when it believes it discovers, outside the concept A, a predicate B foreign to the concept A, which it nevertheless believes to be connected with that concept? [B14]

In the case of geometry, X = space. Space is what the understanding relies on when it sees the necessary truth of predicating “enclose a triangle” of “three non-parallel lines”

Space thereby makes synthetic a priori knowledge possible in geometry. Similarly for time with regard to motion.

Outer sense: The sense by which we are aware of space. The sense whose formal condition is space. Outer does not mean outer in spatial terms — it means outer as in separate from oneself.

Inner sense: The sense by which we are aware of time. The sense whose formal condition is time. This does not mean that outer objects are not experienced in time, but that inner sense is a precondition for this. Inner does not mean inner in spatial terms — it means inner in terms of one’s (private, subjective) mental states.

Kant’s Arguments

I’ll follow Gardner’s breakdown of the aesthetic into the following.

1. Arguments for the proposition that space and time are a priori intuitions 2. Arguments for transcendental idealism, i.e., the proposition that space and time are provided solely by the subject of experience

This is the form of a general distinction in the Critique — or the early part of it (we can see it in the introduction and prefaces as well, if I recall correctly) — namely the distinction between…

- The proposition that the objects of experience are conditioned by the forms of experience

- The proposion that the objects of experience exist in those forms only through experience (transcendental idealism)

Arguments for the a priority of space and time

See also the SEP article: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-spacetime/

Kant breaks down his Metaphysical Exposition of the Concept of space into four parts:

First argument: space is presupposed for outer experience [B38]

We do not learn to perceive objects in space through experience. The experience of objects presupposes that we can relate them to each other – and as outside ourselves – in space. We do not perceive relations and then form the intuition and concept of space on that empirical basis. Rather, we perceive objects already outside ourselves and separated but related to each other. That is, outer experience is impossible without the intuition of space. Therefore space cannot be an empirical intuition, and must be a condition for outer representations.

But be careful. This argument doesn’t fly if it begins with the premise that space is presupposed, because it could be that space and the objects within it are intuited always together. The actual argument is just that space is a condition for the experience of outer objects. The next argument disposes of the possibility that the reverse is also true.

Second argument: we cannot think the absence of space [B38]

We cannot think an object without at the same time thinking space, but we can think space without objects. There is no conceivable perception of objects as somehow existing without space. Therefore, space is a condition of appearances, or “a condition of the possibility of appearances”.

This means that space is not dependent on objects, a conclusion that was not reached in the first arguement.

Therefore, not only is space a condition for outer representations (as found in the first argument), but it is also necessary and a priori, because it is not dependent on objects as they are dependent on it. (If it was a symmetrical relationship, there would be no reason to favour space as a priori, and we might imagine that the representation of space and appearances were mutually necessary).

NOTE: So far, we could still say that space is a concept. All we know at this point is that the representation of space is not empirical.

Third argument: space is unitary and singular [B39]

Space is essentially one. It is not like concepts, whose generality allows multiple instantiations; multiple spaces are merely divisions of the one space. Thus, because all appearances are in space, they are in the same space, the intuition of which underlies all appearances. But the intuition of space also underlies all concepts of space, i.e., individual spatial concepts such as a cube. And as these concepts are not thinkable without space and are therefore dependent on it, space is an a priori intuition underlying both direct intuitions of appearances, and spatial concepts.

It also follows that space is a representation of an object, and not a general concept. In other words, it is an intuition, while also underlying intuitions; but though it underlies spatial concepts, it is not itself a concept because it doesn’t have the feature of generality.

Fourth argument: space as an infinite given magnitude [B39]

We cannot perceive or imagine – that is, we cannot form any kind of representation – of the edge of space. It necessarily goes on forever, because this is an inescapable feature of the intuition. Anyone with a passing interest in physics and cosmology has heard about the expanding universe, and has probably struggled to think the boundary of spacetime. We struggle because a boundary has two sides. This is just what a boundary is.

Kant was, of course, writing before such notions, which in any case might be argued are actually mathematical artefacts which do not impinge on Kant’s argument here.

Also, space is infinitely divisible. It is impossible to represent a smallest division without representing a final length or volume, which could conceivable be divided again.

From these premises it follows again that space is not a concept, for although a concept can conceivably be instantiated an infinite number of times, a single object falling under the concept cannot be infinitely extended. Take the concept of a sphere. Whichever way we look at it, it has a boundary, and we represent it in space, therefore it is not infinite in extent. But surely we can conceive of its infinite division? Yes, but this will go for any concept of an object in space, i.e., this infinite divisibility is not a property of the concept.

**Regarding arguments 3 and 4, see here: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/kant-spacetime/#ConOurRepSpa

The Argument From Incongruent Counterparts [PROLEG 286]

Say there are two gloves exactly alike except that one if left-handed and the other is right-handed. How do we understand this single difference between them, such that one cannot fill space in the same way as the other. Leibniz said that space is a relation between objects, but this cannot explain the difference here, for imagine that there was nothing else in the universe except these gloves, and then the left-handed glove disappeared; the right-handed glove would still be right-handed, such that if the left-handed glove re-appeared, they would differ just as before. It is our relation to the objects, such that we represent the lonely right-hand glove as maintaining its right-handedness internally, that determines orientation. Therefore space is not a construction around objects, as Leibniz held, but is intrinsic to objects – to appearances. Furthermore, we understand orientation completely intuitively. Left- or right-handed: that’s all you can say, and this is not made intelligible using any other concepts.

The Argument From Geometry [B40]

- Geometerical propositions are synthetic, so (without experience) they cannot be based on concepts, which produce only analytic knowledge

- Geometerical propositions have the character of necessity, so they cannot be a posteriori

Therefore, geometrical propositions are a priori intuitions.

Further investigation is required here; it’s a big topic

Some Thoughts on the Arguments

Second argument

We can neither think away space nor objects. Any thought of empty space will actually have something in it. If you think of a giant empty room or a spherical universe, the image you will use to represent it will be an object in space, viz., a cuboid or a sphere. The next step one might take could be to think away those boundaries; does that get us to the thought of empty space? I don’t think so, because my thoughts in that case always seem to alight on something like my own hand stretching out into the void. Or I picture myself – my physical body – standing (how?) in space. Or at the very least I imagine a point of view and myself at the centre, which always entails embodiment (does it?) Essentially, I think, there is always some reference in the form of an object in space. [Adorno p228]

This implies what we might expect, that the relation between objects and the forms of space and time are reciprocal, symmetrical, coextensive. The experience or intuition of space is as dependent on spatial particularity as vice versa.

The a priori and a posteriori, spontaneity and receptivity, are two aspects of a single faculty that centres around experience.

[Adorno p227] [See also Andrea Kern, “Spontaneity and Receptivity” in Analytic Kantianism, p146]

Q. Does this then entail the “shared form”?

So argument 2 for the a priori intuitive nature of space is looking doubtful.

First argument

This is where the precariousness of “pure intuitions” is revealed. They are not a priori as concepts are, because they directly, immediately apply to experience. Indeed, it seems difficult not to think of them as entirely of experience. So it looks like Kant wants to have his cake and eat it.

In terms of psychological development, the most plausible way, to me, of thinking about the experience of babies is that objects come first, and gradually the perception of space builds up around them. This might not work as a knockdown argument against Kant but it calls his argument into question at the very least. [Adorno p226]

And this again shows that Kant is equivocating between space as experienced and space as thought as a concept. It is easy at first to accept that space is presupposed for experience, but this is superficial: space is presupposed for propositions about objects, and for thought about objects; it is not presupposed for experience itself, as shown by baby development. So the mistake here is in concluding from the fact that we cannot think objects without space and always experience things in space, that to experience at all requires that a prior subjective form be imposed on objects. This is not to say that we are not constituted exactly so that we can perceive space, of course. [Adorno p226]

Conclusion

I think Kant’s scheme looks a bit shaky in the light of these objections. The isolation of space, and of time, seems entirely derivative of the concepts, given also the spatiotemporal relations of experience. In other words, there is no room in the middle here for pure intuitions, and the division between a priori and empirical in intuition alone that Kant tries to carry through begins to look contrived.

Kant wants to emphasize the a priority of space, to make it primary. A priori as a concept does carry this meaning, but my criticisms here suggest rather that what is called a priori is as dependent on Experience as vice versa, I.e., all knowledge not only starts with experience but also arises out of it, especially if experience is considered in general, as the central fact of being human. That is, the a priori can come under experience, and questions of actual precedence, priority or basicness are a matter for developmental psychology.

Kant makes too much of the difference, thus opening up a gulf that isn’t there between begins with experience and arises out of experience. As experience is all there is, both are the case. [B1]

TODO: justify the belief that experience is all or that the a priori / empirical distinction can be collapsed or reconfigured.

This all means that space and time are either a) synthetic a posteriori, or b) are both a priori and empirical, such that there is no available distinction, or at least none so radical as the one that Kant sets up, which is something like an independent realm, prior to, more basic than, and more certain than, lived experience in all its particularity.

If these criticisms are right, an important plank in the establishment of the synthetic a priori is knocked out.

The trouble with “pure intuitions”:

Now how can an outer intuition inhabit the mind, which precedes the objects themselves, and in which the concept of the latter can be determined a priori? Obviously not otherwise than insofar as it has its seat solely in the subject, as its formal constitution for being affected by objects, and thereby gaining immediate representation, i.e., intuition, of them, therefore only as the form of outer sense in general. [B41]

Pure intuitions look like merely a “speculative construct” [Adorno p230]

Fourth argument: infinite given magnitudes

It’s difficult to see how space and time could be given as infinite. They appear so only negatively and on reflection. Of course, infinity here just is a negative concept so maybe that’s no argument against Kant. But it is perhaps important that imagining space as positively infinite is just as difficult as imagining it as finite.

Next time: Arguments for Transcendental Idealism (in the strong sense)

QUESTIONS:

- What the hell is the “given” really? How does it relate to appearances?

- What is the difference between sensations and intuitions?